A pet hate of mine is the extent to which our culture conflates being a ‘book lover’ with being really into novels. This view tends to erase the literary merit of non-fiction. I would submit that the ten books on this list, all of them non-fiction, illustrate that nearly everything one could want from a novel can be found in non-fiction. There are compelling narratives that transport us through time and around the world: from our emergence as a species, to a China fighting its way out from under imperial domination, to the coffeeshops of Vienna during its heyday as the intellectual capital of the world, to the “North Korea of Europe”, and also right back here to the UK. We also have characters who were they not real, few authors could conjure: Robert Maxwell, Iris Murdoch, Chiang Kai-Shek and Ludwig Wittgenstein to name just some. We also see more apparently normal people – librarians, miners, printers, advertising executives, an aristocrat fallen from grace, and a schoolgirl – confronting what seems like the end of their world. Most of all these books have people making dramatic, in both senses of the word, choices: between their nation’s heritage and the demands of modern technology, about how to make sense of the horrors of Nazism, as to if it’s acceptable to take money for a good cause from bad people, over who to sack, and whether to let your enemies take your cities or to burn or flood them instead.

In terms of what I’m counting as a “2022 book”, I’m taking it as a book I personally read this calendar month rather than one that was published this year. This is the opposite of what I do for TV, films and podcasts. However, I think it’s probably truer to the less immediate way we read books. That said I try to pick reasonably recent releases to avoid getting into “this Truman Capote guy has a really good turn of phrase” territory. Hence, the oldest book on the list is from 2016.

10. Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through: The Surprising Story of Britain’s Economy from Boom to Bust and Back Again by Duncan Weldon

It’s not exactly an original observation that 2022 has been one of the more eventful years for economic policy making in the UK. Though Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through was published last year, it nonetheless speaks to what has happened since. It points to the limitations of hoping that the country’s economic trajectory can be fundamentally altered through drastic policy changes. As Weldon demonstrates, both the challenges we face and the scope of the solutions to them are deeply rooted in our national history. They cannot be shrugged off or willed away. Without a proper grounding in this history, we have little chance of making the right economic calls in any year.

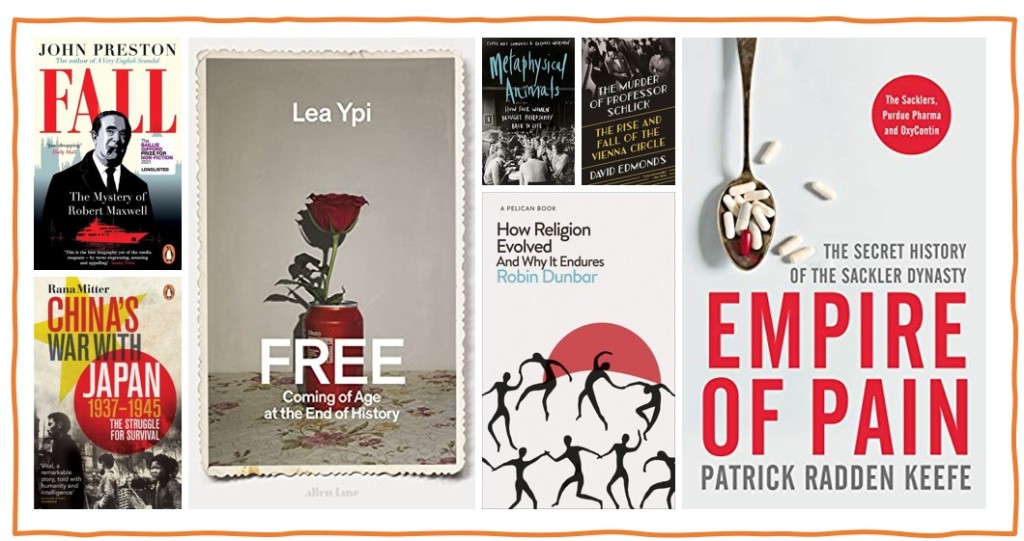

= 8. The Murder of Professor Schlick: The Rise and Fall of Vienna by David Edmonds and Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life by Clare Mac Cumhail and Rachael Wiseman

I’m pairing these two books together as their subjects are intimately connected. The Murder of Professor Schlick recounts the rise of logical positivism in interwar Vienna, whereas Metaphysical Animals tells the story of how a group of four women who studied together in Oxford during World War II recreate against logical positivism and proposed a blend of reinvigorated Aristotelianism and existentialist philosophy as an alternative.

Neither school of thought would accept the idea that philosophical ideas are simple rationalisations of their proponent’s interests. Nonetheless, both Edmonds, and Mac Cumhail and Wiseman show how it was more than chance that these movements emerged when they did. The logical positivists were often liberals/leftists and/or Jews living at a time when either of those identities were more than enough to provoke violent animosity. When one of the most influential logical positivists, Moritz Schlick, was gunned down by a disgruntled student who was likely suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, his killer was hailed as a fighter against ‘anti-German Jewish materialism’ and wound up serving just two years in prison. In this environment, logical positivism’s dismantling of ideas lacking an objective material reality made it a strong solvent against the kind of prejudice and superstition which reached their apotheosis in Nazism.

However, for the Oxford quintet, this went too far. The logical positivists had pared back our intellectual armoury to the point that they had lost the ability to say that Nazi atrocities were objectively wrong. Mac Cumhail and Wiseman also convincingly show how it was only possible for a group of young women to spearhead this counter-movement, because of the World War II. Oxford’s young men were conscripted en masse. Hence, at a stroke the acolytes of A.J Ayer, who by 1939 were the dominant force in the philosophy department, were removed. Left behind were older dons, shaped primarily by traditions which predated logical positivism, to teach philosophy to a student body of which young women were now a much larger part. This cleared space for the protagonists of Metaphysical Animals to pursue their interests in fields like ethics. And crucially, to do so not in terms of better parsing the language used to describe them, but on the assumption that they were studying something real.

It is worth mentioning that Metaphysical Animals is one of two books this year to tell the story of the same four philosophers. There was also The Women Are Up to Something: How Elizabeth Anscombe, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Iris Murdoch Revolutionized Ethics by Benjamin Lipscomb. Which is interesting and as a work of straight biography probably superior. However, I felt it did not engage sufficiently with the ideas of its protagonists, which meant, for my taste, it didn’t give enough sense of the significance of the lives it ably chronicled. For my money that makes Metaphysical Animals the superior book.

7. How Religion Evolved: And Why It Endures by Robin Dunbar

Robin Dunbar is an evolutionary psychologist best known for “Dunbar’s number”, the idea that our brains can only handle 150 friendships. He must be one of the few people with the breadth of expertise and skill as a science communicator to tell this story which stretches across the whole of human history. This does a remarkable job of highlighting the commonalities between what on the surface seem like wildly different manifestations of religious practice.

It also had, for me at least, some genuinely new ideas. For example, the central of role of synchronicity in religious practice is something that once flagged you’ll see everywhere – from hymns sung together to the choreographed bowing of Friday prayers at a mosque, from the shared silence of a Quaker meeting to the tribal rituals which use dancing to the same beat to induce trances.

The thesis that religion has evolutionary origins is something that many believers may be suspicious about. It might seem like an attempt to debunk faith. That concern is basically misguided. If one believes the universe has a creator who intended its inhabitants to one day recognise him, then it would make sense an instinct towards religion but be built into us. More fundamentally, if religion serves such a core psychological and social purpose, then maybe the question is not whether we have religion but what kind.

=5. Kingdom of Characters: A Tale of Language, Obsession, and Genius in Modern China by Jing Tsu and A Billion Voices: China’s Search for a Common Language by David Moser

These two books both tell the story of the evolution of the Chinese language. A Billion Voices manages the remarkable feet of detailing its 3,000-year history in barely 100 pages. Kingdom of Characters instead focuses in on the recent history of written Chinese and the struggle to marry a system based on thousands of characters with technologies like the typewriter, telegram and dictionary which were envisaged with Latin alphabet’s 26 characters in mind. It further zeroes on in the people who made it happen and makes tangible what was at stake for them in this endeavour.

I confess I have put them on this list despite not having finished either. However, they are making an interesting pair as they seem to be heading towards contrasting conclusions. Moser seems to view China’s twentieth century modernisation as a missed opportunity to follow Korea and Vietnam in adopting a phonetic alphabet, whereas Tsu appears to view the same story as an example of tenacious innovation preserving a vital piece of China’s heritage into the present.

4. Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945 by Rana Mitter

The topic of this book is both remarkable in its own right and for being so little know in much of the world. The steps China’s Republican government took to prevent the invading Japanese army consolidating its hold on the country are also unimaginable. They fight not only the Japanese but a large collaborationist army with minimal (and often unhelpful) Allied support, they move their capital further inland multiple times as the multiple cities are captured, they flooded larges sections of the country to literally bog the invaders down, consented to the American firebombing of occupied Wuhan to prevent it being used a base by the Japanese, and, crucially and fatefully, put on hold their hostilities with Mao’s communists.

Mitter is an admirable guide through this tale. It involves genuinely epic history, encompassing some of the twentieth century’s most consequential events, yet Mitter manages not only to recount them, but also reflect their human consequences, and all in a single, medium-length book.

It’s worth reading Forgotten Ally in conjunction with Mitter’s recent book China’s Good War: How World War II Is Shaping a New Nationalism, which looks at how these same events are commemorated and the political ends to which they are put.

3. Fall: The Mystery of Robert Maxwell by John Preston

Like anyone who’s spent time in Oxford, Maxwell often felt like a background character in my life. His grand house on Headington Hill became Brookes’ law faculty, people who’d worked in publishing long enough were frequently still not over what he’d done, and I even studied with someone rumoured to be a relative of his. And yet, while I knew about the pension fraud that prefigured his probable suicide, maybe accidental death, just possible murder, until I read Fall I had no idea of the the full extent of his life (and crimes).

Preston is unsparing about the fact that Maxwell is a bad person. He lies, cheats, bullies, manipulates, steals, is wantonly cruel, narcissistic, turns scientific publishing into a racket, and, in the early chapters, even commits war crimes. This is one of the few narratives in which you’ll be rooting for Rupert Murdoch.

Despite all this, Preston’s Maxwell is never less than a flesh and blood man with thoughts and feelings as human as anyone else’s. Almost despite himself there is something admirable about a refugee tenaciously clawing his way from nothing to the top of British society despite hostility, often rooted in antisemitism, from members of the establishment. There’s also something emotionally vulnerable or even sensitive about him at times. Preston makes a particular effort to uncover the extent to which Maxwell was a product of a foundational trauma: the loss of his entire family in the Holocaust. Clearly this neither excuses nor explain what he later did. It should go without saying that the vast majority of Hitler’s victims who survived WWII did not go on to commit grand corporate fraud. However, it is hard not to see his near sociopathic acquisitiveness – not only of money but of status, esteem and power – as at some level trying to balance out the extent of his early loss. Preston recounts one particularly telling moment, when Maxwell’s son arrived at Headington Hill Hall to find his father stooped over the telly, his face almost touching the screen. The BBC was showing a documentary which featured phots taken at Auschwitz and he was hoping if he looked hard enough, he might catch a final glimpse of his parents or siblings.

2. Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty by Patrick Radden Keefe

Before reading this, my view would have been that Radden Keefe’s previous book Say Nothing, a Shakespearean tale of death, intrigue, compromises and secrets set amidst the Northern Ireland Troubles, was likely an unmatchable achievement. Well, it turns out literary lighting does strike twice.

Empire of Pain argues that the hundreds of thousands of deaths that resulted from the US opioid epidemic can be traced back to one family: the Sacklers. Across generations they have built a pharmaceutical empire, which came to rest on sales of oxycontin. This drug that was supposed to eliminate chronic pain, but instead created millions of addicts. Radden Keefe traces how much successive generations of Sacklers knew and how directly involved they were in the crucial decisions. Indeed, one of the most infuriating parts of the book is the notes on sources, which is full of details on how the Sacklers tried to obfuscate the truth and bully people into not telling it. That said, more than a story of direct guilt, it becomes one of complicity, of how people and institutions in the orbit of the Sacklers find themselves corrupted by the lure of the family’s wealth.

1. Free: A Child and a Country at the End of History by Lea Ypi

There is a famous feminist slogan: “the personal is political”. Free demonstrates that the inverse is also true. Lea Ypi was born in Albania, when it was still known as the “North Korea of Europe”. Her school days are filled with lessons on the genius of Enver Hoxha’s brand of Stalinism. She implicitly accepts that Albania is the one true hold out of socialism, and is unphased by her family darkly mentioning people going away to “university” for long periods for unspecified reasons, and even whispered rumours that the Soviet Union has collapsed. Then one day in 1994, it is suddenly announced that one party communist rule will end and Ypi is forced to confront the fact her government, her country, and even her own family are not what she thought they were.

Ypi is a professor of political theory at the LSE and though the book follows a narrative structure, there is also a cogent argument weaved throughout it. She wishes to challenge a triumphalist narrative that the fall of communism marked Albania’s liberation. This is not to say that she is apologising for Hoxha’s regime. She is unflinching about its repression. However, she presents the arrival of capitalism in the country as a destabilising force. The security of a planned economy was replaced by rapacious impersonal forces out for private gain – corrupt officials, criminal gangs, and the managers of newly privatised firms looking to cut costs. This marked the start of the exodus of Albanians to Western Europe that continues to the present and the country was only pulled back from the brink of a civil war by the deployment of thousands of Italian soldiers.

However, what makes this book so special is that even if you don’t agree with Ypi’s thesis, and personally I find a loss of state capacity a more convincing explanation than marketisation for the travails of post-communist Albania, it still transports you into a particular moment of history. To continue a theme, Ypi has a skill for manifesting people, places, relationships, and moments on the page which rivals that of most novelists. And it is used in service of conveying experiences which are clearly etched into the author’s memory. You thus get these rich subplots like how because her mother is part of a family that was politically influential in pre-communist times, a committed Thatcherite, and, apparently, rather formidable, her father winds up being elected as an MP for the right-wing anti-communist party, despite his socialist instincts. This contradiction only grows more acute once he is given a minister portfolio with responsibility for overhauling the nation’s ports and must grapple with the expectation that he will make them economically viable, even if that means laying-off the bulk of their primarily Romany workforce. This at once draws on the understanding Ypi has instilled in her readers of her father’s character and the dynamics within her family, whilst also guiding us through Albania’s recent history and pushing us to ask questions about our political principles.

The portrait of Albania which emerges by the end of Free is not a happy one. The recent stories throughout the British press about Albanians trying to cross the English Channel in small boats have unfortunately also probably contributed to the impression that it is a depressing place. However, Free also underlines what a deeply fascinating place it is and what a rich and complicated history it has. Mostly as a result of reading it, I wound up visiting for the first time. Between beautiful old Ottoman cities, the impressive mountains of the north, the vineyard and olive tree filled countryside of the south, and peculiar relics of the Hoxha era – not to mention people who seem to genuinely welcome visitors – it is, in my opinion at least, one of the best destinations in Europe. Hopefully Free will be a way into its history for many more people.

- A Billion Voices

- Clare Mac Cumhail

- David Edmonds

- David Moser

- Duncan Weldon

- Empire of Pain

- Fall: The Mystery of Robert Maxwell

- Forgotten Ally

- Free

- How Religion Evolved

- Jing Tsu

- John Preston

- Kingdom of Characters

- Lea Ypi

- Metaphysical Animals

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Rachael Wiseman

- Rana Mitter

- Robin Dunbar

- The Murder of Professor Schlick

- Two Hundred Years of Muddling Through